Creating a Safe Space for Neurodivergent Children to Thrive

/A home is a place of rest and comfort, providing a sense of belonging. It is full of elements that we interact with daily- texture, lighting, furniture. A beautiful aspect of being human is that we all have unique experiences with these tactile elements. Even better, we can design our home these elements to facilitate more comfort and joy. Lately, our studio has been thinking specifically about how home design can improve the experience of Neurodivergent children within their own homes.

Our health and wellness-focused interior design studio works with families to create soothing spaces that support everyone in the home. We've found that boosting the wellbeing of a child will, in turn, increase the wellbeing of the parents and care providers. When we hold space for our loved ones, we can begin to find ways to coexist with peace and ease. It's critical to understand that no singular solution works for everyone, so facing challenges with empathy is key to understanding the unique needs of the child and family. We approach building healing spaces through human-centered home design modalities, prioritizing human interaction with the built environment. For children who may struggle to communicate their needs verbally, it is essential to create a healthy and comfortable environment to support their mental, physical, emotional, and sensory wellbeing.

Some ideas on creating a safe space for a neurodivergent child to thrive:

Offer Choices. Through adjustable and adaptable features, you can empower your child by offering choices to meet their needs.

● Adjustable, thoughtful lighting: Dimmer switches can offer autonomy and create a customizable experience to meet a child's shifting needs.

● Reconfigurable furniture: an interior designer can help create a layout suitable for furniture that a child can freely rearrange themselves. Modular seating, for example, is easy to customize and move within a space to suit the ever-shifting needs of everyone in the household.

● Privacy vs. open space: Consider a bed with curtains or a canopy to offer a safe, private space for a child to find comfort and solitude.

Make it intuitive. Designing an intuitive space can help your child interact with their environment, providing a greater sense of comfort and independence. A great example of this at work is at the Bancroft Raymond & Joanne Welsh Campus in New Jersey. KSS Architects created visual psychological cues throughout the campus, such as a sensory trail and specific textures and colors related to designated spaces.[1]

● Utilize visual cues. The rug pictured above brings in references to the natural world while creating a known pathway and added safety in shared spaces.

● Create spaces designed to help with transitions utilizing psychological cues. For example, if your child is hesitant to go outdoors, consider a sunroom with expansive views to the outdoors so they may watch from a safe space until they are ready to go outside.

Consider materials.

● A home designer can help you source high-quality materials that can withstand heavy handling and potential emotional episodes.

● A highly sensitive child might also be sensitive to odors from adhesives, stains, paints. Wellness-focused home designers can help source non-toxic low/no VOC materials.

● Thoughtfully selected textures and colors can create a soothing, tactile experience. Individuals respond to textures and colors differently, so it is best to utilize samples to assess the physical response between the residents and any proposed materials.

Keep the senses in mind.

● Appeal to unique sensory needs. Because neurodivergent children may have different sensitivities that fall under hypersensitive or hyposensitive, the interior design team should work collaboratively with parents and caregivers to create an individualized strategy.

● Weighted blankets can aid in creating a therapeutic experience for a child. Our studio has worked with families to design custom weighted blankets in natural and organic materials.

● A well-designed bedroom or playroom can incorporate sound-reducing walls. If you are not ready for remodeling, consider acoustic panels, white noise machines, or heavy, interlined draperies to customize the sound experience.

● Many people have specific sensitivities to color temperature. Our studio recommends the residents experience and respond to the proposed color temperature of the light before installation. Consider an "all off" switch for the power in each room, which turns off all power to provide ease for a child sensitive to hums and electromagnetic waves.

● Incorporate artwork: Art can help influence our emotional experience, as viewing art can have mood-boosting effects. Curate a positive experience for a child by selecting artwork that considers their interests.

Incorporate Biophilic Design.

Biophilic design aims to make healthy and comfortable interiors by meaningfully incorporating natural elements into our home design and work environments. We've found that the healing power of the outdoors is one of the best ways to facilitate a healthy environment. Healthcare studies have reported that exposure to nature can reduce stress, lower blood pressure, provide pain relief, and contribute to healing and recovery from illness. [2]

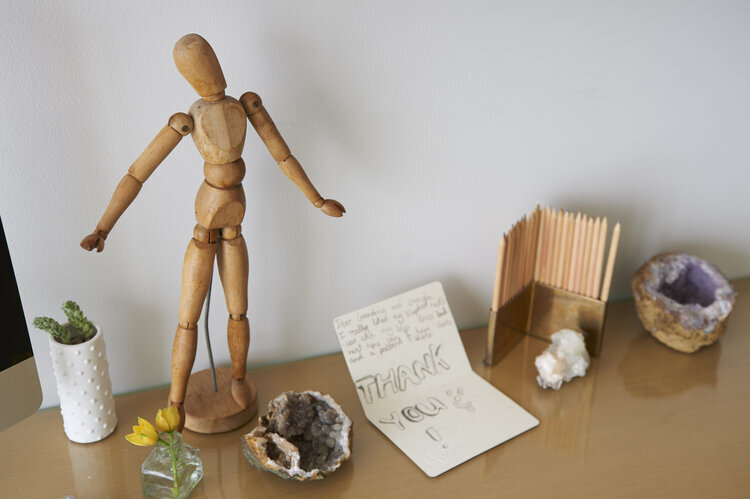

● Utilize nature within the child's space. You can do this using indoor plants, decorating with found objects from nature, or sourcing furniture made from natural, sustainable materials.

● Evoke a sense of nature through items like art, wallpaper, or other nature-inspired decor items.

● Consider designing a room with a view of the outdoors so your child can observe and respond to natural processes like the shift of daylight or changing seasons.

We know that home design can help support a healthy, happy environment for growing children and that personalized supportive environments can be especially helpful for the wellbeing of neurodivergent children. The CDC has estimated that one in every 42 boys and one in every 189 American girls are on the Autistic spectrum. Mindful and empathetic design practice empowers us to create spaces that provide comfort and inclusivity, encourage independence, and improve mood. Creating spaces that consider different needs reduces environmental stressors and triggers, maximizing space for children's strengths to shine.

Sarah Barnard is a WELL and LEED accredited designer and creator of environments that support mental, physical and emotional wellbeing. She creates highly personalized, restorative spaces that are deeply connected to art and the preservation of the environment. An advocate for consciousness, inclusivity, and compassion in the creative process, Sarah’s work has been recognized by Architectural Digest, Elle Décor, Real Simple, HGTV and many other publications. In 2017 Sarah was recognized as a “Ones to Watch” Scholar by the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID).

[1] Bancroft Raymond & Joanne Welsh Campus in New Jersey is a learning center for individuals with neurological challenges, autism, and intellectual and developmental disabilities. The facility was designed by KSS Architects and completed in 2017. [2] Robert Ulrich (1884) facilitated a study of patients recovering from gallbladder surgery and assigned them randomly to hospital rooms. All rooms had windows, though some had a brick wall view, where others overlooked a tree grove. The patients assigned to the rooms with the brick wall view had slower recovery times and greater dissatisfaction with their care than their tree overlooking counterparts